HANDEL Concerto Grosso in C major (“Alexander’s Feast”), HWV 318

performed by Symphony Orchestra of The Bavarian Radio

KAY Pietà

There is no other known recording of this piece! We believe the BPO was the first ensemble to record this piece since its premiere in 1958!

Click here to learn about the Pietà sculpture created by renowned artist, Michelangelo.

MOZART Violin Concerto No. 4 in D major

Watch two young artists perform the virtuosic first movement of Mozart’s Violin Concerto with the BPO.

Esme Arias-Kim, 2020 Sphinx Competition winner

Esme Arias-Kim Bio

BPO Assistant Conductor, Jaman Dunn, interviews Esme Arias-Kim

Maria Sanderson, 2016 Sphinx Competition winner

Maria Sanderson Bio

Discover more musical performances by the BPO on our Music for Youth Education Hub!

IBERT Divertissement

performed by the WDR Symphony Orchestra

Imagine this: you’re a composer and you want to create an epic symphony. It’s gotta be something awesome, with all the bells and whistles (perhaps literally) that you can think of. Just the idea of it gets you excited. So you get set to start writing it: you make your coffee, get the lights just right, open your composition book to the first blank page and… then what?

How do composers do it? How did Beethoven, for example, create his Ninth Symphony, a piece of music that takes 70 minutes to perform? How do you choose which note comes after the one you just wrote down? Take that dilemma and apply it to an orchestra’s worth of instruments and you’re really facing an uphill battle. Oh and don’t forget things like rhythm, dynamics, meter, key… it’s quite a lot, isn’t it?

If you think of composition like that, it becomes impossible quickly. Luckily, composers don’t think like that. That would be like an author trying to write a novel one letter at a time without any kind of advance plan. Not a recipe for success.

Composers rely on development to create music. Development is a big word for a simple thing: take an idea and mess around with it. Build something big using small, versatile things. Like bricks or legos, but with music.

Entire symphonies can be created by establishing core musical ideas, called themes, and then essentially riffing on them. But wait: what’s a theme? What do I mean when I say “musical idea”? A theme could be anything from a memorable melody to a very basic series of notes, like dun-dun-dun-duhhhh (Beethoven’s Fifth, if you weren’t sure). Composers can use these themes and combine them to make new ones, modify them to bring the listener to a new part of the piece, or use them to signify external ideas (motifs! Remember those?)

Ok, but how does it work? Like, how do you mess around with a melody without going off in crazy directions and sounding random? I’ve got two versions of an exercise for you to help you get used to this idea and become composers yourself. If you’re able to play a single octave major scale on an instrument, then do this first version of the exercise. If not, no worries: skip this first one and go to the second. And yeah, doing both would be even better! I see you, overachiever.

This first exercise requires your instrument, so get it out and tuned up. Choose a really easy major scale to play, something you know really well and can do automatically. Ready?

Let’s change the way we think about a major scale. Instead of a rigid series of notes that you have to play to make your teacher happy, think of it as a melodic theme instead. What you have is a series of notes that are played in a very specific order. How might you develop this theme? Remember, development is about playing around with a theme, changing it and modifying it. The simplest way to do that is to change the order of notes! Why do scales have to be played in the same order all the time, right?

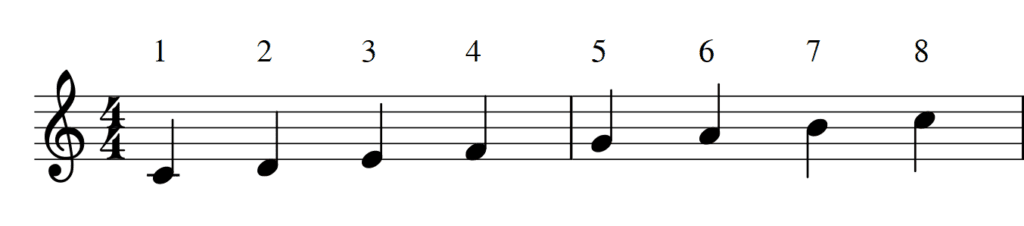

To do this, take your scale and add a number to each note that corresponds to its order. Something like this:

You’ve got eight notes. Hooray, what a beautiful theme. Let’s mess with it and change the order. Here’s a really common example of how you can do this:

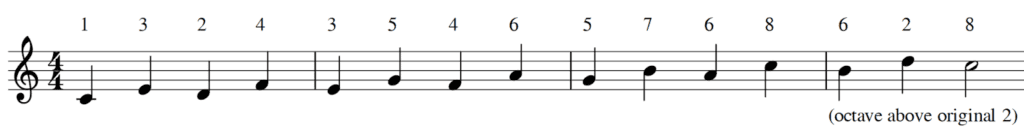

Woah ok, now we’ve got more stuff. Look what I did: I took that scale and changed the order. Do you see a pattern? If you play it, you’ll probably hear it. The pattern is play the first note, skip the second, play the third, and then play the second, and so forth. Do you see how I created something new out of our major scale theme? All I did was change the order of notes into a new pattern, but you can hear that this new example was created from the original theme, which was our major scale. This is the very essence of musical development: creating new ideas using old ones.

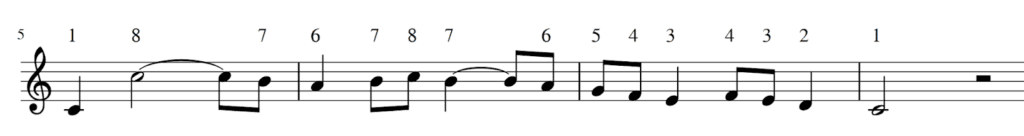

My example was pretty basic. There’s lots you could change, like rhythm, the notes themselves, or the instrument it’s played on. With a full orchestra, the possibilities are endless. It’s your turn now: find a new way to develop this scale. It can be as simple or as complex as you want. I’m going to do one more just to show you where you can go with this:

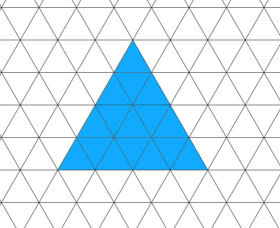

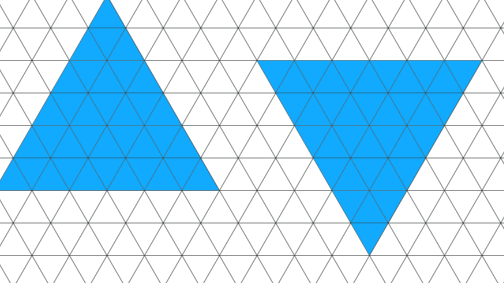

Ok, don’t have an instrument available? This is for you. Go to https://maxwellito.github.io/triangulart/. Click on “start a new canvas”, and then click on “Go!”. What you should see is a grid of triangles, with some common art tools on the bottom. What we have here is a tessellation art tool. What that means is that you can create art using a single shape! Makes sense right? Kinda like the legos/bricks analogy I used earlier. Ok, check this out: we can only use triangles, which seems limiting, but you can do something like this:

Start by making a bigger triangle:

Now we mess around with it. Make another one next to it, but upside-down:

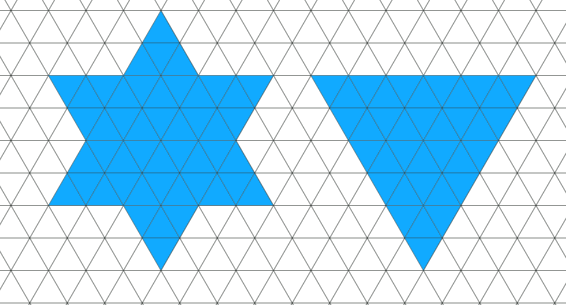

And then merge them together! You can’t just drag that triangle over unfortunately, but create that same triangle over our original triangle, leaving everything filled in. It’ll look like this:

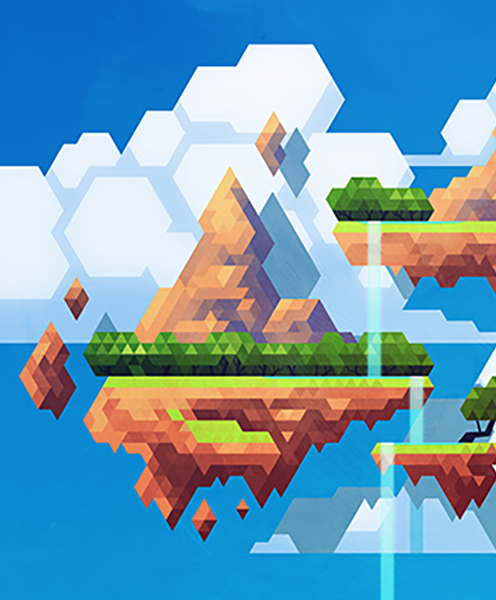

Ta-da! Mind blowing, I know. But you see what I did there, right? We’re using only triangles to create new shapes. First it’s simple, just bigger triangles, but then we use those to create a new, more complex shape. It’s the concept of development in a nutshell: use small ideas and play around with them to create new ones. The above example is a really simple example of this. If you look at the following image, you can see how far you can take this idea:

(this is in reference to a certain video game. The biggest kudos to you if you know what it’s from).

Ok so I’ve already taken up a ton of your time, but I need to tie this to the concert. There’s a reason I’m talking about development, after all. We’re going to focus on the Mozart, and I’ll just give you brief examples of musical development within the piece. Hopefully with those above exercises, you’re already primed to recognize this process beyond what I share with you now.

Concertos are great examples of development because there’s a clear distinction between the orchestra, who presents ideas, and the soloist, who can develop upon them. Here are two examples of this:

The piece starts with the orchestra establishing a primary theme:

The orchestra then goes on to establish a few other ideas before the soloist enters. When the soloist does enter, he enters with that primary theme, with a slight variation at the end:

This is a pretty basic example, but the solo part is filled with these kinds of things. It’s what makes listening to the music interesting: you can recognize when something is being developed and appreciate the virtuosity of the soloist.

One more example to show another method by which a theme can be developed. The following theme is first established by the orchestra after the primary theme, but before the soloist enters:

The soloist later plays this theme, but the notes are changed to turn it into a minor key, a distinctly different sound:

So, as you can hear, it’s not just about changing the order of notes, but you can also change the notes themselves to suggest different harmonies while still referencing the original theme.

I hope that by turning your ears on to this compositional device, you’ll begin to pick up on it in all different kinds of music, not just classical. The establishment of a musical idea and its subsequent development is one of the most fundamentally creative aspects of music.

Discussion Questions:

- After learning about the concept of development, does the Mozart concerto sound more or less complex to you? Either answer is valid, but explain why. How does it change your understanding and appreciation of the music, for better or worse?

- Using timestamps, provide another example of development from another movement of the concerto or from another piece on the program. Even if you’re unsure, try your best to listen for developed themes. It helps to go back to earlier parts of a piece to reaffirm whether or not you’ve heard a certain melody before, and to compare it to what you’re currently hearing.